Special Education Related Services

Contact

Kathryn Cook, MS, CCC-SLP

Coordinator of Related Services (Occupational Therapy, Physical Therapy, Speech/Language Pathology, Vision and Hearing Services.)

kcook@medford.k12.ma.us or 781-393-2317

- Translator/Interpreter Services

- Speech, Language and Hearing

- Occupational Therapy

- Physical Therapy

- Vision Services

- Secondary Transition

- Assistive Technology

Translator/Interpreter Services

All ELL Parents are entiltled to translator services if necessary. We have Haitian-Creole, Portugeuse, Spanish and Chinese interpreters in house. Low-incidence populations may request services, but may have to wait until the district can contact outside services. Please call the ELL Office at 781-393-2348 or 781-393-2341 for further information.

Speech, Language and Hearing

Purpose

Our purpose:

- To educate parents, guardians and caregivers

- To give tips to build communication skills at home

- To answer frequently asked questions

- To provide a list of department staff members

This website provides information (including definitions, related target skills, and suggestions to support skill development) regarding the four following subgroups:

1.) Speech:

- Articulation involves making the sounds in a language that are related to speech.

- Fluency is the continuity, smoothness, rate, and effort of speech production

- Phonology is the aspect of language that relates to rules that govern the structure and sequencing of speech sounds. For example in English, the ng sound, as in sing, will never appear at the beginning of a word

2.) Language:

Communication using spoken language, written language, or other symbol systems. Language includes content (vocabulary, concepts), form (sounds, word endings and beginnings, grammar), and use (the function of language within context also known as pragmatics).

- Receptive Language is the understanding of language input.

- Expressive Language is language output.

- Social/Pragmatic Language is how we use our language. According to the American Speech, Language, and Hearing Association (ASHA), social/ pragmatic language involves three major communication skills: Using language for different purposes, changing language according to the needs of a listener or situation, following rules for conversations and storytelling.

3.) Hearing:

A hearing disorder is the result of impaired auditory sensitivity of the physiological auditory system.

4.) Pre-literacy and Literacy:

Speech and language are the foundation for reading abilities. Specific skills include: Spoken Language, phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary development, fluency, reading comprehension.

What is an SLP

What is an SLP?

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) work to prevent, assess, diagnose, and treat speech, language, social communication, cognitive-communication, and swallowing disorders in children and adults. Additionally SLP’s provide aural rehabilitation for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing.

What Does it Mean to Be Certified?

Being “certified” means holding the Certificate of Clinical Competence (CCC), a nationally recognized professional credential that represents a level of excellence in the field of Speech-Language Pathology (CCC-SLP).

Those who have achieved the CCC—ASHA certification—have voluntarily met rigorous academic and professional standards, typically going beyond the minimum requirements for state licensure. They have the knowledge, skills, and expertise to provide high quality clinical services, and they actively engage in ongoing professional development to keep their certification current.Certificate holders are expected to uphold these standards and abide by ASHA’s Code of Ethics.

How are school based services different from services in other settings?

| School-based Service | Medically-based Service | |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | is governed by state and federal law and team decision | is determined by 3rd party payment and/or individual therapist |

| Purpose | is to enable school participation | is to remediate disability |

| Service Delivery | is in the Least Restrictive Environment (including contextually based direct service and/or consultative services) | is typically direct individual or group clinic-based treatment |

| Focus | is on what will most efficiently facilitate participation in the school environment | is on treatment to remediate a disability,medical condition, or injury |

Speech

Articulation

Articulation

Articulation involves making the sounds in a language that are related to speech. Sounds can be substituted, left off, added or changed. Young children often make speech errors as they learn the sounds in a language. For instance, many young children make a “w” sound for an “r” sound (e.g., “wabbit” for “rabbit”) or may leave sounds out of words, such as “nana” for “banana.” Not all sound substitutions and omissions are speech errors.

Instead, they may be related to a feature of a dialect or of an accent if your child is bilingual.

What is developmentally appropriate?

Sounds acquisition occurs along a developmenal progression. The earleist acquired sounds include: p, b, m, n, w, h, g, k, t, d, and y, followed by f, and “-ing.” Later occuring sounds include: l, v, “ch,” “sh,” “j,” z, s, r, “th” as well as consonant blends (such as “sl” in “slide” and “tr” as in “train”).

Should I be worried if my child hasn’t acquired these sounds?

Not necessarily. When thinking about your child’s speech, consider his or her intelligibility. The term intelligibility refers to how much a listener can understand the speaker. As children learn to talk, their ability to be understood to those around them steadily increases. Generally speaking, by the time your child is 4, he or she should be understood by family, friends, and acquaintances.

How can I help my child learn the speech sounds?

- Model good speech for your child using a moderate rate of speech.

- When your child produces articulation errors, repeat the utterance using correct speech sounds. For example, if your child says, “I see the tar.” you can repeat their utterance correctly by saying, “Oh, yes! I see the car, too!”

- Don’t directly imitate your child’s errors. Some of the cute things our children say are very precious to us. But don’t inadvertently reinforce the incorrect productions.

- Read to your child. It’s amazing how much this accomplishes. Use reading as a way to surround your child with the targeted sound.

- Play with your child. Spend time talking with your child in play, while you model the correct productions very simply, using revision. Talk to your child as you go through your daily routine. This is a chance to model many correct productions, use revision, and stimulate language development, too.

- Gain your child’s attention before speaking so that he or she can pick up important cues about the way you use your lips, teeth, tongue, etc. to produce speech sounds.

- Get down to your child’s level as you speak so that your child can hear and see your speech productions more easily.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Should I understand everything my toddler is saying?

A: No. Toddlers are in the process of acquiring speech sounds. They learn best by practicing how to make sounds and how to put sounds together to make words. Since they are still learning, we cannot expect them to be perfect at it. Toddlers are not understood all of the time, even by their parents.

Q: How do you understand what a child is saying when s/he is difficult to understand?

A: Some strategies you can use are to learn how the child talks (identify “patterns” of errors that they make over and over), ask questions (starting with general questions like, “are you talking about something I can see? and gradually becoming more specific, offering choices, asking them to show you what they are talking about, asking them to say it in a different way (or using different words), and repeating back what you did understand so that you and your child are focused only on the small part of the message that you did not understand.

Q: Do boys and girls develop speech sounds at different rates?

A: All children develop speech sounds at different rates; however, girls do tend to develop speech sounds faster than boys.

Additional Links for Parents

Games for parents and children

Additional games for parents and children

Articulation Apps

Fluency

Definitions:

Fluency:

Fluency is the continuity, smoothness, rate, and effort of speech production.

Stuttering:

Stuttering is a communication disorder that is characterized by the production of dysfluencies, or disruptions in the production of speech. Everyone is dysfluent sometimes. Examples of this are repeating words (e.g. I-I don’t know) or using fillers like “um” or “uh.” However, excessive dysfluency can impact a person’s ability to communicate effectively. In addition to producing frequent dysfluencies, a person who stutters may also appear “out of breath” when speaking or experience physical tension in the muscles that produce speech.

Types of dysfluencies may include:

| Type of dysfluency | Examples |

|---|---|

| Prolongation of speech sounds | Wwwwhere is my bag? |

| Repetition of sounds, syllables, or whole words | T-T-T-Tell me again, please. |

| Use of a series of interjections/fillers | Can I um um um go to my friends? |

| Blocks: where speech may be completely stopped until the person is able to complete the word | Mom, I’m leaving. Long pause-Bus is here. |

The ASHA website (http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/stuttering/) states that the cause of stuttering is unknown; however, genetics may play a part. Stuttering may also be impacted by neurological, environmental, developmental, and emotional factors.

Cluttering:

Cluttering is a communication disorder characterized by rapid and/or irregular speaking rates and excessive disfluencies. A person who clutters may sound “jerky” with inappropriate pauses, or as if he or she is not sure about what to say. Additionally, other symptoms are often present, including language or phonological errors and deficits in attention. Unlike people who stutter, those who clutter demonstrate little to no physical tension or secondary behaviors when speaking, as well as limited awareness of their irregular speech pattern.

Developmental Stuttering:

Per the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association’s (ASHA) website (http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/stuttering/), signs of developmental stuttering first appear between the ages of 2 ½ years and 4 years. A smaller number of children may not begin stuttering until elementary school. Among elementary school-aged students, stuttering is 3-4 times more common in males than in females.

How stuttering develops is variable. Some children may have more dysfluencies at the onset (or beginning). Other children may become more dysfluent gradually over months or years. The severity of dysfluency in children can also vary greatly from day to day and week to week. More stable symptoms of stuttering are seen in older adolescents, teens, and adults who stutter.

Per ASHA, 75% of children who demonstrate developmental stuttering eventually stop, some within a few months of the initial onset of dysfluencies. It is difficult to say for certain if a child’s dysfluency will continue into adulthood. Other people may also stutter for years and then improve. Per the National Stuttering Foundation’s website (http://www.nsastutter.org/), about 1% of the general population is estimated to stutter.

Parent Tips:

- Stuttering Foundation’s Tips for Talking with Your Child

- Stuttering Foundation’s Video “Stuttering for kids by kids”

- Stuttering Foundation’s EBook “Sometimes I just stutter”

- Stuttering Foundation’s Video “Stuttering and your child”

- Stuttering Foundation’s “If you think your child is stuttering”

Additional Information for Parents:

- ASHA webpage for Stuttering

- ASHA webpage for Childhood Fluency Disorders

- Stuttering Foundation’s webpage for Cluttering

- Nationals Stuttering Foundation

- National Stuttering Foundation- “Elementary School-Aged Kids”

- Stuttering Foundation

- Super-Duper Publications’ “Stuttering” handout

Frequently Asked Questions:

1. I think my 3-year old child is starting to stutter. Should I be worried?

Per the Stuttering Foundation (www.stutteringhelp.org), about 5% of children go through a period of stuttering that lasts six months or more. This is referred to as developmental stuttering. Seventy-five percent of those children will recover by late childhood. As a parent, there are ways you can interact with your child to encourage fluency during this stage of developmental stuttering: If you think your child is stuttering

2. My elementary school-aged child stutters. Is there anything I can do as a parent to help?

As a parent, there are many ways you can assist your child in developing more fluent speech, including reducing demands, modeling good communication/slow rate, diminishing time pressures, and giving your child your undivided attention when possible. Please see the Parent Tips section of this webpage for links to parent resources on the Stuttering Foundation’s and National Stuttering Foundation’s websites.

3. What is the difference between stuttering and cluttering?

Per the ASHA foundation, as compared to individuals who stutter, people who clutter talk better under stress, when interrupted, on longer sentences, and in a foreign language. Additionally, individuals who clutter read unfamiliar texts better, do not seem to notice or care how he or she talks, do not have remissions in speech disorders, talk worse when calm, and do not pay attention to what is said. Only about 2% of all individuals with fluency disorders are considered “pure clutterers.” Stuttering and cluttering can coexist.

4. Are boys or girls more likely to stutter?

In elementary-aged children, stuttering is 3-4 times more common in males than females.

5. My family member stutters. Does that make my child more likely to stutter?

The ASHA website (http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/stuttering/) states that the cause of stuttering is unknown; however, genetics may play a part. Stuttering may also be impacted by neurological, environmental, developmental, and emotional factors.

6. Are there any famous people who stutter?

There are many famous people who stuttered and went on to have successful lives including Emily Blunt, James Earl Jones, Winston Churchill, Marilyn Monroe, James Stewart, Carly Simon, Bob Love, John Updike, and King George VI. The Stuttering Foundation provides an extensive list: Famous People who Stutter

Practice Ideas for Home:

Check out our games, apps, and books below:

But how would you work on fluency using games, apps, and books you might ask? Simply have your child use their most reliable fluency strategies during the activity of your choice.

Games:

Scattegories, Headbands, Guess who, Apples to Apples, Zingo, Uno, Boggle

Apps:

Articulation Station, Toca Boca, My Play Home Lite, Name Things

Books:

The Very Hungry Catterpillar, Green Eggs and Ham, The Tiny Seed, Chicka Chicka Boom Boom

Phonology

What is Phonology?

Phonology is aspect of language that relates to rules that govern the structure and sequencing of speech sounds. For example in English, the ng sound, as in sing, will never appear at the beginning of a word.

What are Phonological Processes?

Phonological processes are patterns of speech sound errors that children use to simplify speech as they are learning to talk. For example, a child may delete final consonants from words as in cu for cup.

Some common phonological processes used as children are acquiring the sound system of a language may include:

| PHONOLOGICAL PROCESS (Phonological Deviation) |

EXAMPLE DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Velar fronting | “Kiss” is pronounced as “tiss” “Give” is pronounced as “div” |

| Final consonant deletion | “Home” is pronounced a “hoe” “Calf” is pronounced as “cah” |

| Weak syllable deletion | Telephone is pronounced as “teffone” “Tidying” is pronounced as “tying” |

| Stopping | “Funny” is pronounced as “punny” “Jump” is pronounced as “dump” |

| Cluster reduction | “Spider” is pronounced as “pider” “Ant” is pronounced as “at” |

| Gliding of liquids | “Real” is pronounced as “weal” “Leg” is pronounced as “yeg” |

Adapted from COPYRIGHT ©1999 CAROLINE BOWEN

Should I be worried if my child still uses phonological processes?

Not necessarily. Generally, most phonological processes disappear by a by age 5.

What is phonological awareness?

Phonological awareness is the ways in which speech can be manipulated and divided into smaller parts. This includes rhyming, segmenting syllables and sounds within words and blending them together to form words. Improving phonological awareness skills has been shown to help with reading readiness skills.

How can I help my child?

Use good speech that is clear and simple for your child to model.

Sing simple songs and recite nursery rhymes to show the rhythm and pattern of speech.

Acknowledge, encourage, and praise all attempts to speak.

Engage Your child in the following types of activities.

Rhyming and alliteration activities

• Have your child point out the rhyming words in a poem

• Substitute poem words then ask your child for a rhyming word for the replaced word.

Oral Blending Activities

• Say a word in parts. For example, instead of saying brush your teeth, segment the sounds of words as in B – R – U – SH your teeth.

• Play a guessing game. Tell your child, “I’m thinking of an animal.” Sound out the parts of the word as in, ‘It’s a g – i – r- a-ff- e.

Oral Segmentation Activities

• Ask your child questions such as, “Can you tell me the last sound in breakfast?”

Phonemic Manipulation Activities

• Help your child differentiate sound position in words by counting the sounds in words.

• Play word games by replacing the first sound in a word with another sound. For example, replace the first sound in the word “hand” with /s/.

FAQs

Q: Should I correct my child when they produce the sound errors?

A: Not necessarily. It can be frustrating for a child to repeatedly try to imitate a sound that they are not yet ready to produce. Instead try to model the sound or sound patter for them, emphasizing the correct production. For example, if a child says, “A tat” (A cat), you can repeat the word correctly several times, “A cat. Yes, I see the cat. What a pretty cat!”

Phonology Apps

Language

- Receptive and Expressive Language

- Narrative/Expository Discourse

- Social/ Pragmatic Language

- Non-Verbal Communication

- Play Skills

Receptive and Expressive Language

Definitions:

Language:

Communication using spoken language, written language or other symbol systems. Language includes content (vocabulary, concepts), form (sounds, word endings and beginnings, grammar), and use (the function of language within context also known as pragmatics). Receptive and Language are discussed below.

Receptive Language:

Receptive language is the understanding of language input. This includes understanding vocabulary, concepts; big / little, on/ off, few/ many, directions, prefixes/suffixes, word endings; unhappy vs. happy, hat vs. hats, questions, grammatical structures, stories, facts, and implied information.

Expressive Language:

Expressive language is language output. This includes expressing single word vocabulary, concepts; big / little, on/ off, few/ many, prefixes/suffixes, word endings; unhappy vs. happy, hat vs. hats, directions, questions, grammatical structures, stories, facts, and implied information.

Language Disorder:

According to The American Speech Language Hearing Association (ASHA), a language-based disorder is characterized by problems with age appropriate written and spoken language. If a child speaks two or more languages and has a language disorder, he/she will have a language disorder in both languages.

Language Difference:

Language differences are the result of the normal process of learning a second language. As a child learns a new language, their first language will influence their second language development (this is typical and expected). If a child speaks two or more languages and exhibits language differences, they will not exhibit difficulties in both languages.

Language Development:

Language begins to develop at birth when an infant learns to cry in order to receive food, comfort, and company. Children vary in their development of speech and language skills. However, they follow a progression of skills as they learn language. The skills listed below indicate the order that many children develop these skills. If a child is not developing on track, he or she may not be able to fully access or participate in their school curriculum.

Typical Progression of Skills:

- Plays peek-a-boo and pat-a-cake

- Listens when spoken to, attends to spoken information and directions

- Understands words for common items such as “cup”, “shoe”, “juice”

- Responds to requests

- Imitates sounds and words

- Uses one or two words independently

- Knows a few body parts and can point to them when asked

- Follows simple directions (“Roll the ball”) and understands simple questions (Where’s your hat?”)

- Enjoys simple stories, songs, and rhymes

- Points to pictures when named in books

- Acquires new words on a regular basis

- Use some one or two word questions (“Where’s kitty?” or “Go home?”)

- Puts two words together (“More cookie”)

- Has a word for almost everything in their environment

- Uses two or three word phrases to talk about and ask for things

- Names objects to ask for them or to direct attention to them

- Answers simple, “Who?” “What?” and “Why?” questions

- Talks about activities at daycare, preschool, or friends’ homes

- Uses sentences with four or more words

- Pays attention to a short story and answers simple questions about it

- Hears and understands most of what is said at home and school

- Uses sentences that give many details

- Tells stories that stay on topic

- Communicates easily with other children and adults

- Develops an understanding and use of varied language forms (grammar)

- Understands factual information and makes connections with previous knowledge

- Understands and expresses figurative language such as idiomatic expressions (e.g., Let the cat out of the bag)

What can I do at home to help my child

The chart below lists specific language skills, how they are demonstrated receptively, how they are demonstrated expressively, and links to home activities that can be used to help your child.

| Skill | Receptive | Expressive | What can I do at home to help my child? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vocabulary | understands words used within their environment | expresses single words within context | Label everything around you including your actions,

Narrate your actions and daily activities in language that your child understands, Narrate your child’s actions and activities Read to your child Encourage older children to read on their own Play naming games (e.g., name 10 animals) |

| Utterance length | understands utterances of increasing length and complexity,

understands varied language intents; requests, directions, comments |

uses utterances of increasing length and complexity

uses language for a variety of purposes or intents ranging from commenting to sharing to greeting |

Affirm your child’s utterance and encourage their language development by expanding on their initial utterance. For example, if child says; “ball“, parents says “play ball“, or red ball. If child says “red ball“, parent says; “Yes. I see the red ball“. As child’s language advances, with questions and models, you can request that child add details to their utterances; “I see the little red ball” “Do you see the little, red ball on the table?”.

Acknowledge your child’s comments with a contingent comment. For example if child says, “I like monkeys“, parent can respond, “Yes! You saw monkeys at the zoo“. Encourage child to imitate adult’s expanded utterance. Ask the child closed, rather than open ended questions; “Do you want apple juice or prune juice“? Create opportunities to encourage your child’s talking. Place (favorite) items slightly out of reach to encourage them to request it. |

| Basic concepts | understands words that describe location (e.g., on, off), time (before, after), order (first, then), quantity (many, few), attributes (e.g., big, little). | uses these words effectively | Talk about the environment around you and your child

Describe size, shape, location, color, texture during every day activities. Describe where things are rather than pointing. Expand the level of your vocabulary when you describe things (e.g., big, huge, gigantic). |

| Directions | follows directions, one step, two step, related (e.g., open your binder, get out a pencil, and write your name), unrelated (stand up, turn around, touch your head). | gives directions of increasing complexity | Give your children directions at a level that they understand.

Encourage your child to understand or give direction one step beyond their current level Here are some directions to use at home for play/practice: 1-step-directions 2-step-directions 3-step-direction 1 conditional-directions |

| Questions | responds to; yes/no, who, what, where, when, why, how questions. | asks; yes/no, who, what, where, when, why, how questions | Model questions at a level appropriate for you child understands, starting with what questions.

As you read to your child, ask questions aloud that encourage curiosity and comprehension (e.g., I wonder who is knocking at the door). When talking with your child, ask questions that require higher level thinking such as: why do you think…? what will happen next? how will this change what’s going to happen? |

| Morphology

(word endings/word beginnings) |

understands how word endings and beginnings (suffixes and prefixes) change word meaning, for example: the s in cats indicates that there is more than one cat, the un in unhappy changes the meaning of the ‘root’ word. | uses word endings and word beginnings (suffixes and prefixes) | Explain rules of language to your child such as more than one item is plural (he has two cats), past, present, and future tense.

Correct errors in your child’s language as they come up such as “two feet” not “two foots.” Use pausing and intonation to emphasize what you want your child to learn. Explain the meaning of prefixes and suffixes such as “dis” (means not as in “disorganized”), “ful” (means full of as in “wonderful). |

| Grammar | understands the rules of language to infer meaning when listening to sentences | uses the rules of language to construct sentences and convey the intended meaning | Model a variety of sentence structures within everyday activities. For example, you might say, “I see ____, I like ____, I found____, We are _____, They feel____, Open the ___, Is he____?, Where do _____ live?

When your child makes a grammatical error, provide a clear corrected model with encouragement to imitate. For example, if you child says, “I see dog” you might say “I see the dog.” If you notice grammatical errors in your child’s writing, help them edit it. Encourage your child to self-edit their written work. |

| Narratives | understands a story,

understands important elements of a story, such as characters, setting, problems, solutions, sequence of events |

tells a story (beginning with recall of past events, then sequencing stories, followed by telling stories that include critical information such as characters, setting, supporting details, problem, solution.) | Talk about your day using sequence words such as first, then, before, after, next, finally, last.

Read to your child and discuss the events of the story. Discuss the character, the setting, the problem, the actions, the ending of the story. Encourage your child to make predictions, ask questions, draw conclusions, talk about their favorite part of the story. Make up fantasy stories with your child. Use graphic organizers to help children recall information from stories. Links to organizers are below. |

| Facts | understands facts | can convey facts | Play fact or opinion games with your child. For example, “Is this a fact or opinion? Chocolate is the best dessert.”

Point out books that contain facts verses books that tell stories or give opinions. When reading with your child, see if you can remember three facts and if he / she can remember three facts. When watching programs on television, discuss facts verses opinions. |

| Inferencing | understands implied information and uses clues to draw conclusions | uses background knowledge to draw conclusions, provide clues, tell riddles, jokes, and use idiomatic expressions, understand context clues | While reading books or watching movies and TV shows, ask your child to predict what they think will happen next. Some questions you might ask include: “How do you think he/she feels right now?” What do you think he/she is going to do?” “Why do you think he/she is going to do that?”

From a young age, encourage your child to attempt to answer their own questions before providing an immediate answer. As your child gets older, encourage them to ask questions while they read. Help your child discover the answers to these questions (e.g., search for the answers online, have them ask their teachers). Provide opportunities for your children to practice visualization (imagining pictures) while reading or listening to stories. You might ask: “What do you think the character ____ looks like?” “What does their house look like?” “What did you picture ____ doing in the story?” Practicing visualization helps children to “picture” what is going to happen next in a story. This supports inferencing skills. Graphic organizers can help students to make inferences. Some examples of graphic organizers |

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q: How can I find time to help my child with their language skills?

A: Use time when you are already with your child to practice their language skills. Language can be practiced in the car, while shopping, cooking, cleaning, around the dinner table.

Q:Why won’t my child talk about school even when I ask questions?

A: The reasons can be many but may be related to the type of questions you are asking and the time you are asking them. Many children need time to decompress from their school day before they are ready to talk. Asking specific questions can also help when trying to help your child open up and remember their day. It seems oftentimes, that kids are most ready to talk, when it is bedtime. Perhaps this is because they are avoiding going to sleep but you can plan ahead for this by preparing for bedtime a bit early so you have time to talk before they fall asleep.

Q: My child’s teacher said that he is “a visual learner”. What does this mean?

A: Every child has their own unique learning style. Some children learn most easily by looking (visual), others by listening (auditory), and still others by doing(kinesthetic). Teachers work to differentiate their instruction so that children with different learning styles have opportunities to learn in the way that works best for them. Oftentimes, children who struggle with language will learn better through another modality such as visual or kinesthetic.

Narrative/Expository Discourse

A narrative or story is a report of connected events, real or imaginary, presented in a sequence of written or spoken words, or still or moving images, or both.

Expository discourse is a discourse that explains or describes a topic. Some of the major types of expository discourse include: comparison (compare/contrast), causation (cause/effect), procedural (temporal sequence), problem/solution, collection/description (descriptive), and enumeration.

Some of our students participate in aspects of the Story Grammar Marker Curriculum under the direction of his/her speech-language pathologist (SLP). The following link lists some key concepts from that curriculum. Please contact your child’s SLP with specific questions about your child’s speech-language targets and program.

https://mindwingconcepts.com/pages/about-us

Narrative Related Apps

Preschool/Elementary School

- Storyboard That -A graphic organizer and storyboard creator that reinforces English and history concepts in elementary school and beyond. Students can create and retell their own narrative.

http://www.storyboardthat.com/help/storyboard-creator

- All About Me -Create a story about you! Add your own pictures and audio about yourself. $.99

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/all-about-me-storybook/id426201106?mt=8

- Puppet Pals- Create your own puppet show using pictures from your environment. Free-$1.99

Puppet Pals

- Pic Collage – Create movable pictures on a background (think felt board) using your own pictures.

https://pic-collage.com/

Middle/High School

- StoryBoard That- a graphic organizer and storyboard creator that reinforces English and history concepts in elementary school and beyond. Students can create and retell their own narrative.

http://www.storyboardthat.com/help/storyboard-creator

- Google docs/classroom/sheets/drive- A free Web-based application in which documents and spreadsheets can be created, edited and stored online. Students can create and edit their own typed responses to writing prompts or book summaries.

Google.com

- Quizlet- Trains students via flashcards and various games and tests.

Quizlet.com

- Sparknotes- A site that helps you understand books, write papers, and study for tests.

Sparknotes.com

Recommended Books/activities

Preschool/Elementary School

- The Tiny Seed

- The Very Hungry Caterpillar

- A Bad Case of the Stripes

- Caps for Sale

- Where the Wild Things Are

- Harry the Dirty Dog

- If you Give a Mouse a Cookie

- Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No-good, Very-bad Day

After reading: Complete a graphic organizer using pictures or words

Middle/High School

- Devise a target reading schedule for the summer reading book (s) of your choice. (Use the summer calendar link below to help with this)

- Complete Written Summary or Graphic Organizer

- MCAS practice items: Answer multiple choice questions, and write short open response prompt.

http://www.doe.mass.edu/mcas/testitems.html

Summer Calendars

Preschool/Elementary School

Middle/High School

https://docs.google.com/document/d/12hNiDz7Cecj0zOhZrVX2FTn2y9sRGMH6ZvCKVbjIQSM/edit?usp=sharing

Social/ Pragmatic Language

Key Terms:

Social/ pragmatic language is how we use our language. According to the American Speech, Language, and Hearing Association (ASHA), social/ pragmatic language involves three major communication skills:

Using Language

Using language for different purposes, such as:

greeting (e.g., hello, goodbye)

informing (e.g., I’m going to get a cookie)

demanding (e.g., Give me a cookie)

promising (e.g., I’m going to get you a cookie)

requesting (e.g., I would like a cookie, please)

Changing language

Changing language according to the needs of a listener or situation, such as:

talking differently to a baby than to an adult

giving background information to an unfamiliar listener

speaking differently in a classroom than on a playground

Following Rules

Following rules for conversations and storytelling, such as:

taking turns in conversation

introducing topics of conversation

staying on topic

rephrasing when misunderstood

how to use verbal and nonverbal signals

how close to stand to someone when speaking

how to use facial expressions and eye contact

These rules may vary across cultures and within cultures. It is important to understand the rules of your communication partner.

from: http://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/Pragmatics.htm 11/9/2016

Additonal Terms:

Nonverbal communication is one aspect of social/pragmatic language skills. Click here for more information about nonverbal communication.

Play skills are an important part of language development, and some social/pragmatic language skills can be addressed by targeting specific play skills. Click here to learn more about language and play.

Non-Verbal Communication

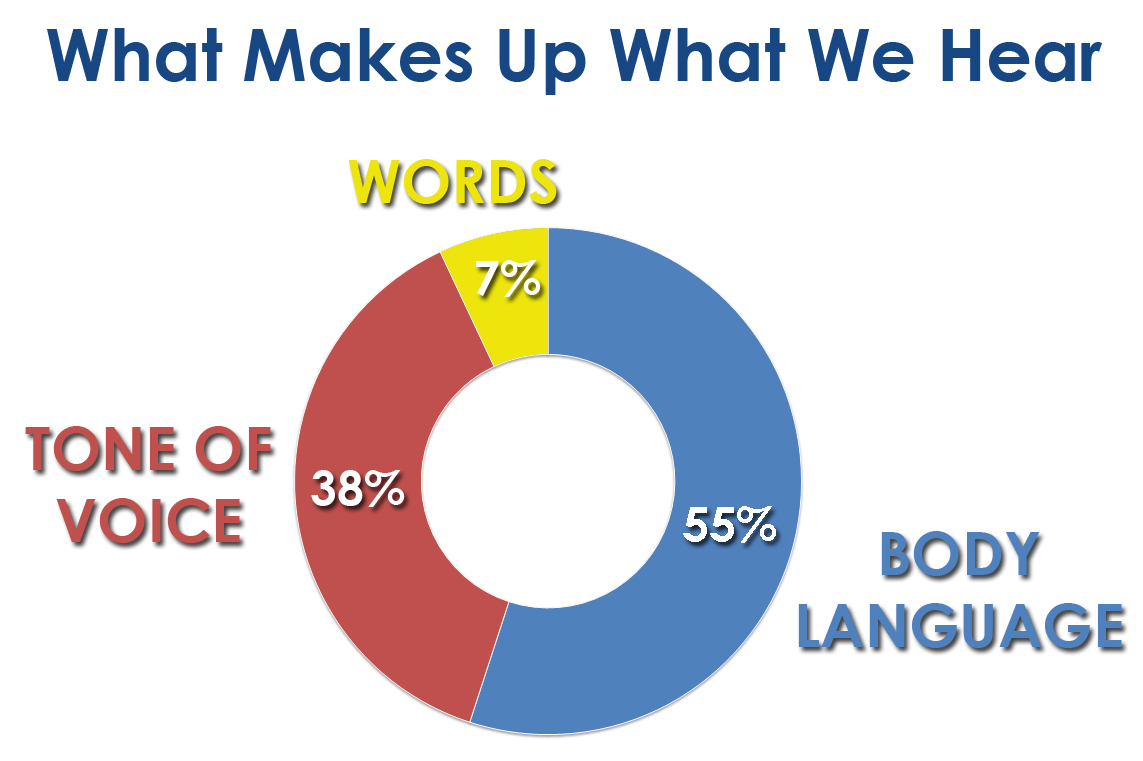

Much of what we say to each other is not just expressed with words, but through gestures, body language, tone of voice, and voice melody. Nonverbal communication can support what you say (such as smiling while telling a friend, ” I like that shirt!”), replace what we say (such as a head nod for “yes”), and even contradict what you say (such as eye rolling while saying “I can’t wait to get started on that.”).

- Students with social/pragmatic language difficulties often have difficulty using and interpreting non-verbal communication.

- These students may have:

- Difficulty reading and using body language and facial expression: These students may appear overly serious and use a ‘flat’ tone of voice OR may be overly expressive and not understand when to use those tones.

- Difficulty understanding sarcasm: These students may be very literal, as they are not “keyed in” to the tone of voice, but rather focus only on the exact words used.

What can I do to help?

- Be specific with your words: Try to avoid using language that is too general; it can leave room for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

- Example: Instead of saying, “Pay attention,” be specific, and say, “Listen to mom’s words, this is important,” or ,“Look at the directions on the top of the paper.”

- Watch a television show clip with the volume off: Make a game of trying to guess what is happening in the show. Re-watch with the volume on and discuss the similarities and differences of your version and the actual version.

- Play carefully with sarcasm: Our students may react opposite to what you mean or may get frustrated with their difficulty understanding it. If a situation arises where sarcasm is used, use it as a teaching opportunity. Explain to the student what is said and what is really meant, and direct the student to listen for the different voice tones and watch for the body language involved.

Play Skills

Language development and play skills go hand-in-hand. Below are some ways you can build language skills (expressive, receptive, and social/pragmatic language skills) through play.

Pre-K and Kindergarten: Building Language & Literacy through Play

Play in Autism Spectrum and and Social Communication Disorders: Encouraging Pretend Play in Children with Social Communication Difficulties

Hearing

Hearing is the process of picking up sound and attaching meaning to it.

Hearing loss, and the resultant decreased exposure to spoken language, can contribute to deficits in the areas of receptive and expressive language, ability to hear and make speech sounds, academics, and social functioning.

Hearing loss is described by type, degree, and configuration.

Types of Hearing Loss:

- Sensorineural (inner ear)

- Conductive (middle ear)

- Mixed (combination of areas)

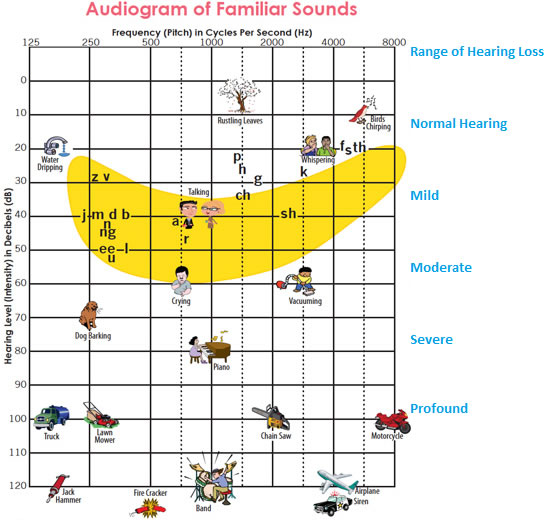

Degrees of Hearing Loss:

- Mild (20-40 dB loss)

- Moderate (40-70 dB loss)

- Severe (70-90 dB loss)

- Profound (90 dB and greater loss)

Configuration:

Configuration is the shape or pattern of the hearing loss as shown by an audiogram.

Hearing loss is also described as:

- Bilateral / Unilateral (affecting both ears or one ear)

- Symmetrical / Asymmetrical (degree and configuration are the same or different in both ears)

- Progressive / Sudden (becoming worse over time or happening quickly)

- Fluctuating / Stable (changing over time or staying the same)

Audiogram:

An audiogram is a graphic representation of a person’s hearing responses, or thresholds, which are the softest sounds a person can detect. Looking at an audiogram from left to right, the sounds get higher in frequency or pitch. Looking from top to bottom, the sounds increase in intensity or volume.

Graphic credit: www.jtc.org/parents/ideas-advice-blog-comments/audiogram-of-familiar-sounds

Simulations of Listening with a Hearing Loss:

- For simulations of different degrees of hearing loss with different sound sources, click here. (Source: Starkey Hearing Technologies)

- For a simulation of listening through hearing aids and Hearing Assistance Technology (HAT) click here. This is a 6 minute video, the first 3 minutes demonstrate listening through hearing aids, and the last 3 minutes show listening through hearing aids and a personal FM system. (Source: Jim Bombicino, Vermont Center for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing / Regional Consultant Services)

Additional Information for Parents:

Literacy

Speech and language are the foundation for reading abilities. Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) are able to apply their expertise in speech and language development to support students in their reading and literacy skills. These skills include:

- Spoken Language: reading requires a student to understand spoken words, sentences, and conversation/connected speech

- Phonemic awareness: allows for the ability to hear, blend, segment, and manipulate sounds (pic-nic, p-i-c-n-i-c)

- Phonics: the relationship between sounds and letters

- Vocabulary development: learning new words

- Fluency: reading out loud with expression, accuracy, and appropriate pacing

- Reading comprehension: the ability to think about and understand the text including identifying story elements, cause/effect, main idea, point of view, character traits, and awareness of various genres

Speech and Language Pathologists support literacy in the classroom through:

- Prevention: SLPs help parents and teachers prepare students for reading by encouraging the growth of language skills.

- Identifying at-risk students: SLPs recognize the signs of early reading difficulty such as sound awareness, vocabulary, and syntax weaknesses. They are then able to direct the child’s team appropriately.

- Assessing: SLPs evaluate basic skills that predict reading abilities such as the ability to identify initial sounds, blend and segment sounds, and rhyme.

- Intervention: SLPs recommend activities to teachers and parents to strengthen students’ literacy skills, as well as giving suggesting for modifying work.

Make Sharing Books Part Of Every Day:

- Read or share stories at bedtime or on the bus.

- A Few Minutes is OK—Don’t Worry if You Don’t Finish

- Talk or Sing About the Pictures

- Let Children Turn the Pages

- You do not have to read the words to tell a story and it’s okay to skip pages.

- Show Children the Cover Page

- Explain what the story is about.

- Show Children the Words

- Run your finger along the words as you read them, from left to right.

- Create voices for the story characters and use your body to tell the story.

- Make connections: Talk about your own family, pets, or community when you are reading about others in a story.

- Ask Questions About the Story, and Let Children

- Ask Questions Too!

- Use the story to engage in conversation and to talk about familiar activities and objects.

- Let Children Tell the Story

Apps:

- Starfall (free): Allows for children of all ages to practice their reading skills including letter/sound identification, decoding, and fluency using visuals, games, and other engaging activities http://www.starfall.com/

- EPIC! Books (free): Allows children and parents to access of over 25,000 free high-resolution fiction and nonfiction books for children of all ages. Offers a “read to me” option and audiobooks. https://www.getepic.com/?msclkid=6813fe62c0f715c1d321a4a607bc3f6e&utm_source=bing&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=US%20-%20Site%20Trials%20-%20Brand%20-%20Alpha&utm_term=epic%20ebook&utm_content=epic%20ebook

- Reading Magic (free): Helps children develop phonological awareness (including blending and segmenting) and decoding skills.

- Phonics Fun on Farm (free): Provides games targeting development of phonemic awareness, letter-sound relationships, writing and letter recognition, spelling, and reading fluency.

Books:

- Brown Bear Brown Bear What Do You See

- Goodnight Moon

- The Very Hungry Caterpillar

- Llama Llama I love you

- Chicka Chicka Boom Boom

- The Giving Tree

- Dr Seus Books

- Corduroy

- Harold and the Purple Crayon

- Pete the Cat

- The Snowy Day

ASL Videos

Occupational Therapy

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was enacted “to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living.” (IDEA §300.1) Occupational therapy, as a related service, is provided when required “to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education.” (IDEA §300.34).

“School-based occupational therapy practitioners are occupational therapists (OTs) and occupational therapy assistants (OTAs) who use meaningful activities (occupations) to help children and youth participate in what they need and/or want to do in order to promote physical and mental health and well-being. Occupational therapy addresses the physical, cognitive, psychosocial and sensory components of performance. In schools, occupational therapy practitioners focus on academics, play and leisure, social participation, self-care skills (ADLs or Activities of Daily Living), and transition/ work skills. Occupational therapy’s expertise includes activity and environmental analysis and modification with a goal of reducing the barriers to participation.” From AOTA, 2017 ‘Brochure for School Administrators: What is the Role of the School-Based OT Practitioner?’

Occupational therapy practitioners collaborate, adapt, design, support, and contribute to the development of programs and implementation of initiatives in ways that address the needs of all students, including students who are at risk, in addition to their roles in supporting individual students under IDEA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. Their unique skill set and perspective focused on health and wellness, self-advocacy, and meaningful participation in life makes them uniquely qualified to participate in a wide range of building, program and district-level activities.

Occupational Therapy Resources

- Parent brochure: ‘What is the Role of the School-Based Occupational Therapy Practitioner?’

- ‘Occupational Therapy in School Settings’

- Additional parent resources related to occupational therapy for children and youth can be found on the AOTA website

Physical Therapy

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was enacted “to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living.” (IDEA §300.1) Physical therapy, as a related service, is provided when required “to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education.” (IDEA §300.34).

School-based physical therapy practitioners are physical therapists (PTs) and physical therapy assistants (PTAs) who use knowledge and expertise in the areas of mobility and physical access to assist students to physically access and participate in all aspect of the educational environment and program.

In addition to their roles in supporting individual students under IDEA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, physical therapy practitioners can share their knowledge on a broader scale through building or district-wide professional development/staff training to build capacity of teachers, parents and others to address needs of the larger student population, including those who are at risk to promote health, wellness and fitness.

Resources

Vision Services

Medford Public Schools provides consultative and direct services for students with vision impairment or blindness who require vision services via an IEP or 504 Accommodation Plan. Vision services include services provided by a Teacher of the Visually Impaired (TVI), and services provided by a Certified Orientation and Mobility Provider (COMP). MPS contracts with Perkins School for the Blind to provide both TVI and O&M services to MPS students within their school setting.

Secondary Transition

Assistive Technology

Assistive technologies provide creative solutions that enable students with disabilities to be more independent and productive.

The definition of assistive technology is extremely broad. An assistive technology device is any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of children with disabilities. Assistive technology devices range from low/no tech (e.g., use of a highlighter pen or bold-lined paper for a child with executive function challenges or vision impairment) to high tech (e.g., a sophisticated speech output augmentative communication device for a child who is non-verbal) and everything in between. An assistive technology service is any service that directly assists a child with a disability in the selection, acquisition, or use of an assistive technology device (IDEA, 2004).

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) 2004 requires schools to consider each student’s need for assistive technology whenever an Individualized Education Program (IEP) is written. In addition, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act require schools to provide assistive technology for students with disabilities, when required to assure equal access to school programs and services.

The principal reason for providing assistive technology is to enable students to meet the instructional goals set forth for them. These tools can also help students with disabilities participate more fully in both the academic and social activities in school. School personnel look at the tasks that each student needs to accomplish, the difficulties the student is having, and the ways that various devices might help the student better accomplish those tasks (MA Dept. of Elementary & Secondary Education, 2012).

IEP and 504 Teams consider each student’s need for assistive technology using a collaborative decision-making process. Most often the occupational therapist (AT) or speech-language pathologist (AAC) (see section on AAC below) leads the team in the evaluation process but there may be other team members with specific areas of expertise who may take the lead in specific situations. For example, a special educator or reading specialist may take the lead if the student’s primary need area is reading, a physical therapist may take the lead if positioning and/or mobility are the primary needs of the student (remember, any item that improves function is considered ‘AT’; a wheelchair, walker or gait trainer are all considered AT under the federal definition above).

Occupational therapy is concerned with ‘occupational performance’ – that is, ensuring students are able to participate meaningfully across school contexts and activities. When evaluating a student’s need for assistive technology, occupational therapists lead the team through a process of identifying the student’s strengths and needs as well as analyzing the features of the activities, environments and contexts in which the student participates that may support or hinder the student’s occupational performance. The team then collaborates to identify potential assistive technology that may help the student to achieve the instructional goals set forth for them and participate in school. When more specialized or complex AT is being considered, the educational team will seek out consultation from others who have experience in the area of AT being considered.

Click here for more information on the role of occupational therapy in the AT evaluation process

Link to MPS AT Resources: https://sites.google.com/medford.k12.ma.us/medfordpublicschoolsat/

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

Contact: Kathryn Cook, Supervisor of Speech, Language, and Hearing (Augmentative and Alternative Communication – AAC), scampbell@medford.k12.ma.us or 781-393-2381

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is a category of assistive technology that is addressed by speech-language pathologists (SLPs). AAC can help students with severe speech or language problems to communicate. There are many types of AAC available. The SLP determines a student’s need for AAC through evaluation when recommended by the team.

MA DESE AT/AAC Resources:

- Access to Learning: Assistive Technology and Accessible Instructional Materials

- Technical Assistance Advisory SPED 2018-3: Addressing the Communication Needs of Students with Disabilities through Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

US DOE/US DOJ AAC Resource: